|

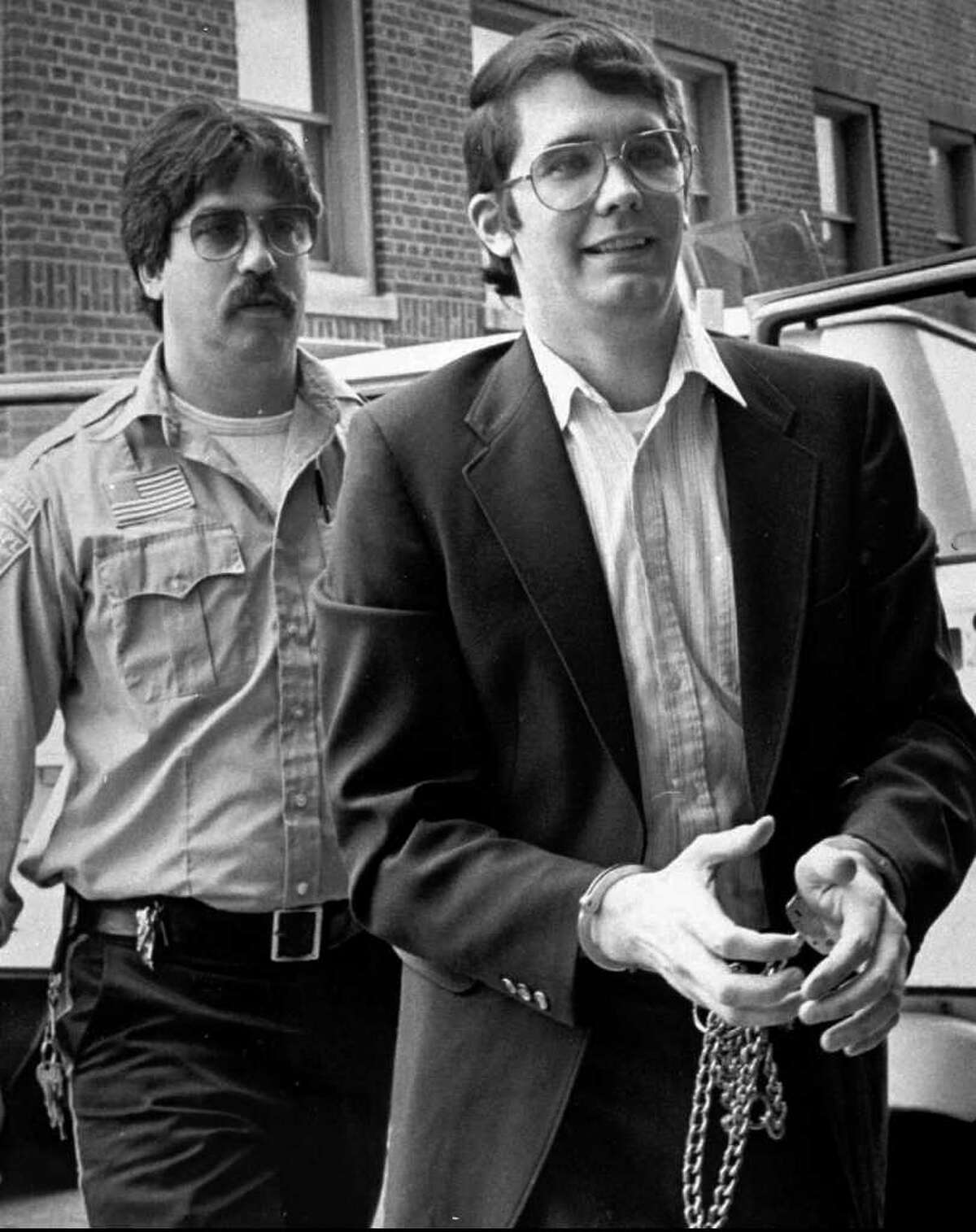

| Michael Ross |

Democrat Governor Ned Lamont, we find from a news

report, “has been pushing for gun restrictions earlier this year, but

the recent legislative session expired in early May without action.” The report

quotes him: “… there are so many illegal guns on the street right now. I’d like

to think we could have done a better job here in Connecticut and send a message

far afield, especially when it comes to those ghost guns.”

Was Lamont suggesting that the elimination of ghost guns

would have prevented the most recent slaughter of the innocents in Texas? Was

he suggesting that black-market gunrunners would cease and desist their already

illegal activities should the national legislature pass gun laws favored by

Blumenthal and Murphy?

One almost feels indecent in pointing out that ghost guns

played no part in the assault on elementary schools in Texas or Sandy Hook. The

elimination of ghost guns may provide a solution to some problem – but not this

problem.

Another story in today’s paper, “Schumer

rips GOP after school shooting in Texas,” reports that Schumer has

implored “his Republican colleagues to cast aside the powerful gun lobby,” the National

Rifle Association (NRA), “and reach across the aisle for even a modest

compromise bill. Schumer is quoted: “If the slaughter of school children can’t

convince Republicans to buck the NRA, what can we do?”

In the face of a still raw mass murder, Schumer might try to

temper his politicking. Neither of the mass murderers in Texas or Sandy Hook

were responsible gun owners, and it is doubtful that either were dues paying

members of the NRA.

Generally we do not blame bank robberies on banking

associations. Schumer is asking us to believe that, in respect of mass

shootings, it is better to do something – anything, though his plan may not

reduce mass murders or urban killings -- than to “do nothing at all.”

Following the Sandy Hook massacre, Connecticut legislators,

arguing that “something must be done,” passed a slew of legislation regulating

gun sales. Those laws have had no appreciable effect on multiple killings in

Hartford Connecticut, the seat of the state’s General Assembly. And there are

those in the state who argue that if you cannot pass a bill preventing

14-year-old-children in urban areas from shooting other 14-year-old-children in

urban areas, you will not be successful in curbing mass shootings anywhere in

the state.

What might such a bill look like?

In Sandy Hook and Texas, both killers were young men, 18 to

21, from broken households who spend an inordinate amount of time on the

internet indulging their violent tendencies.

The Sandy Hook killer shot his mother, stole her guns, an

AR15, a shot gun, and an automatic pistol with which he killed himself, and

shot his way through the front entrance to Sandy Hook elementary school.

He was a loner, monkish, somewhat withdrawn from school life

and life affirming social interactions. He had no arrest record and there were

no reports that he was under mental duress.

The Texas murderer procured his guns legally, shot his

grandmother in the face and proceeded to an elementary school that was, so to

speak, a gun free zone, where he locked himself in a room with his victims and

opened fire.

What you must do to prevent such occurrences would simply

repeal most of the cherished liberties enjoyed by a citizens who would under no

circumstances enter a school and kill multiple young children.

In both cases, there were no fathers in broken homes to

police lawless sons. Blumenthal, Schumer and Murphy have

yet to suggest a law that would air drop stern and protective fathers into such

households. Nor have they suggested that the freedom to visit internet sites

contributing to moral anarchy across the nation should be curtailed, because

such laws would violate First Amendment rights, cherished by reporters and

political commentators.

Nor have partisan politicians – Murphy, in particular, now seems

eager to entangle all Republicans in the U.S. Senate in a far-fetched moral complicity in mass

murders -- suggested sensible precautions, the hardening of access

to schools, for instance. We post armed interveners in banks because we wish to

prevent bank robberies and secure valuable assets. Are our children less

valuable than our bank account savings?

In the Texas mass murder case, we now know, the school was

not properly hardened to prevent a mass assault; the school’s guard was not present

at the time of the attack; multiple doors were unlocked; police waited too long

before storming the building; neither children nor school staff were taught how

to respond in case of such attacks; the perimeter fence surrounding the school

was easily penetrated; there was no centrally activated room locking system

available – in other words, mistakes

were made.

It may be nearly impossible to prevent every instance of

mass murder in schools, just as it is impossible to prevent all bank robberies.

But illegal activities in both cases can be justly punished. And the most

successful tool of mitigation, we know, is the swift and certain imprisonment

of convicted criminals. Just punishment does deter crime – which is

why Senators such as Blumenthal, Murphy and Schumer provide us with an endless

stream of laws designed to frustrate unwonted activity.

But, as yet, no one is screaming from the rooftops that just

punishment delayed is just punishment denied. Would Blumenthal and Murphy

welcome a reinstitution of Connecticut’s death

penalty for mass murderers?

Likely not, but why not? Connecticut’s Supreme Court years

ago found that even a just capital punishment violated an assumed moral

resistance on the part of Connecticut citizens against capital punishment.

Since then, capital punishment has become a very back bench issue in

Connecticut politics, the legislative equivalent of the sin that dare not speak

its name. Some suspect that moral exemplars among our politicians no longer

believe in the utility of just punishment. It is much easier politically to find

guns rather than murders guilty of and punishable for mass murder.

Comments