Hilliare Belloc’s advice to the rich – “Learn something about the internal combustion engine, and remember: Soon, you will die.”

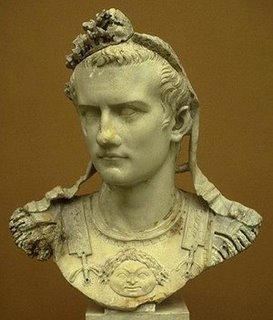

Caligula

So, I have become a ghost, the nearest I shall ever be to a God again; for, in life, I was a God. Divinity, you know, is the highest form of politics. What is higher or nobler than a God? … But wait: Nobility has nothing to do with it, as if nobility and Godliness could ever share the same frame; a God is above that sort of thing … As a former Emperor – now, God and ghost – everything to me was permissible, and understandable. I comprehend by grasping my subject from the inside; nothing was alien to me. I am solid as earth now, though I know it does not seem so to you, because I know everything; I am in everything, and everything is in me. That is how I know; through a process of identity and self revelation. I become the thing I want to know – say, a tree, or a young boy, or a virgin – and then, at will, I revert to Godliness. You, on the other hand, seem very transparent to me. I’ll bet I know what you are thinking. You are thinking: He’s mad …Well, in a sense, you are right. What is permissible for the God is forbidden to men. There are borders; but God is he who transgresses all borders. And in my time, no God/Emperor – there were a few of them -- transgressed more lustily than I … That is all you need to know about God: He is opaque and impenetrable. Nothing can pierce His surface. And yet, He is accessible to men, glad, as they say, to be of service – for a price. And, of course, I – as God – set the price; it is my Godly prerogative. Madness is only Divinity by another name. When Dionysius entered men, he drove them mad, and they knew what it meant to participate in Godliness – much to their surprise … Some lessons come hard, others are hard. Men always think God favors them; pile sacrifices at His feet, and He will look favorably upon you. But God is other than you; the thing so large and so far above you it cannot be comprehended, which is why priests and prophets speak of God in a kind of storied poetry. Since God is ineffable, He must be worshipped … It was my responsibility, while I lived, to convince men that God was not for them; nor was he against them. He was merely indifferent to men. And so, penetrated by God, I was also indifferent to men. One day, I would be laughing with them; the next day, I would have them for my supper. Ah, you understand me! God the cannibal! I know what you are thinking. You are thinking: He is mad … But we’ve been through that. Anyway, all this must bore you. You moderns have gotten away from God, and He, always a slippery fellow, has gotten away from you. You are hiding from each other, playing hide-and-seek, as children sometimes do. You have become practical atheists; perhaps it is better so. You do not know God, and he does not know you. I was a corrective to my time and place. I became God so that men would know God. So, you want God, I said to my fellow men: I’ll give you God, Goddammit! … There is no one like me in your universe, though there have been poor carbon copies. Your world, however, is not much different than mine. Do you know how modern Rome was? Just for a minute, forget all the foreign elements, the window-dressing of the culture that haunts and misleads you, and think of Rome as a modern empire: We had armies, you have armies; we had marriages and divorces – too many divorces -- you have marriages and divorces; we had abortion and infanticide, you have abortion and … not infanticide yet, but you are steadily progressing and some day you will have it; we had condominiums, you have condominiums; we had a plague of lawyers, you have a plague of lawyers; senates, lobbyists, contractors corrupting senators; senators corrupting contractors; publicists, engorged political commentators, queers, actors, musicians, mimes, disturbed artists, drug dealers, witches, savants, priests, even tender young lovers, troublemakers of all sorts – we had them all. And you have them too … Are we so very different then? If you had looked out your condo window on a bright Monday morning in ancient Rome, and saw attorney Livio pounding up the pavement heading to his office near the government complex to file a brief for the widow Rostia, carrying in his hand a laptop computer, breathing heavily – for he had been neglecting his workouts at the gym – and dressed in the height of fashion, splendidly attired in , let’s say, a Pal Zileri suit and a Zenia tie – would you not think you were in any large city in Europe or America, circa 2006? … So then, it is the funny robes that make the man -- and the era too. It is the dress and improvements in technology that puts distance – You call it history – between Caligula the God and, shall we say, Senator Edward Kennedy, about whom your social critic, Gore Vidal, once said, “I do not mind Kennedy; every state should have at least one Caligula.” Thanks, Gore a’preciate it … Distance! So very important! One does not want to get too close to a God, an era or an emperor. That is why I have come to you dressed this way (He appears in modern suit, very conventional), so as to abolish the alienating distance between us. You have a saying: “Don’t be a stranger.” Well now, am I so very strange in these well fitting clothes? I know what you are thinking: You are thinking – he is mad. But we’ve been through all that … Of the twelve Caesars of Rome, I am the one least hedged round by firm facts; though, God knows, rumors abound. It has become accepted lore, through that notorious scold Suetonius, that I thought of nominated my horse to the Senate. But Incitatus was a very bright horse, much more patriotic – and, I may say, less ambitious – than the average senator. And why not a horse to keep company with the horse’s asses? Oh, what I suffered. You don’t know the half of it. Rome was a dead Republic long before I became emperor. In my time, there was no one living who knew the glorious Republic, except in their diseased imaginations. But the Republic had always been an emotive idea, very popular among the people. The Republic, the Republic, the Republic – the Res Publica Romanorum, assassinated long ago by ambition and of necessity. It lasted from the overthrow of the monarchy in 510 BC until Julius Cesar and Octavian put an end to the business in 44 BC. But the Republic was buried with the corpses of the Gracchi brothers a hundred years earlier. After them, mobs and money ruled Rome. It was this corrupted Republic, rotten from the inside out, that turned to Cesar for order and peace. And it was Cesar who delivered to the people of Rome the Republican reforms of the Gracchi -- a Republic, one popular Roman actor friend declared, without the bother of a Republican government. First Julius, then Octavius – then Caligula, the God. It was an inevitable logical development, though some people, taking the libels of Suetonius as fact, persist in thinking me mad. But I was an honest to god God, without subterfuge. Gods must not stand on ceremony with their worshippers. The movement from Cesar to God is not a lateral one; it is an upward thrust that necessarily must change the nature of things. When God appears, dead nature blooms. Before my time, Caesars used to parade themselves before the public as Princeps, “equals among men.” But, in fact, they were far removed from the common folk and simply pretended to be ordinary so as not to alarm those below them, who were more numerous and collectively powerful. Since the death of the Gracchi, Rome was moved only by organized mobs. “Let them hate,” I said, “so long as they fear.” And they feared me – because I ruled by contraries, in the manner of a God. And what does a God have to do with men? God moves men by terror and love. So, to be a God is something different than to be an emperor; and an emperor is different than a Princeps, an “equal among equals.” To be God is to be other. Augustus Cesar established the Cult of the Deified Emperor and promoted it, especially in the new colonies in the Western Empire. Augustus, however, always insisted that he was not divine. The Cult worshiped his numen – What would you people call it? – the personal spirits surrounding him, and his gens, the spirit of his family and ancestors. The Cult of the Deified Emperor languished under Tiberius and came to full flower only under my hand. I made the temple of Castor and Polix in the Forum a part of the Imperial Palace. There I appeared on occasion in a Godly form, magnificently dressed. You cannot tell from my present appearance how awesome I was. My religious policy spread like fire throughout the empire. I replaced the heads of the statues of the Gods at Rome with my own, including, of course, the female deities. The people groveled appropriately and worshipped me, not merely in spirit but in truth; not merely some idea of me, but me myself – in the flesh. Judea, as usual, resisted. A plan to place a statue of myself as Zeus in the Holy of Holies in the Jewish temple at Jerusalem was stalled by the Syrian governor. And Herod Agrippa forecasted riots here in Rome and an insurrection in Judea should my plan go forward. Who needs riots? Since the demise of the Republic, only mobs and money move Rome. And on the point of my deification, it was necessary that Rome remain immovable. I know what you are thinking: He is mad … Rumors and half-baked truths swirled furiously around me. Some said I was mad; these I disposed of. Others whispered I had suffered a mental collapse because I had lived a reclusive life before being thrust on the public stage. Like an actor coming into the foreground from a twilight background, the bright lights of empire and notoriety wounded my mind. Well, reclusive – yes. When one is hunted as a child, in constant danger of death and destruction, one tends to prefer invisibility and solitude. One wants to disappear into the background, or go masked like an actor. Others said I was brilliant, disposing of a sometimes caustic and cruel wit. Philo of Alexandria, the philosopher, was of this mind. Caligula was mad; no, Caligula was a vicious jokester; he was dissolute, arrogant, egotistical, cuttingly witty … So it went. God has many faces but escapes all attempts to imprison him in terrestrial categories. Speaking of jokesters, the comic genius Aristophanes, a real gadfly, once was rebuked by an offended and pious patron. Said the furious patron – who likely was politically connected – “Don’t you take anything seriously?” Aristophanes replied, “Of course, my fine fellow: I take comedy seriously.” In the same way, I took divinity seriously – and found myself utterly alone in an ocean of agnostics. I was serious, you understand, about my Godly prerogatives, which were limitless. Emperors – and still more Gods – are bound only by the limits they impose upon themselves. Is this madness? I think it is extreme sanity. Other emperors before me had plumbed the extent of their powers; only I realized it … My death was disappointingly pedestrian to me. The emperor Tiberius had left Rome very much in the black. I blew through this public fortune quickly, recovered from the Senate some of the imperial powers ceded to it by Tiberius – quite the Republican, Tiberius -- expanded the imperial court, and grievously disappointed the people. I gave them everything but one thing. They had bread and circuses; they wanted a Republic. The people had been spoon-fed the notion that the Republic inhered in the senate, which had become, by my time, thoroughly corrupt. “How I wish,” some near contemporaries misquoted me, “their heads were mounted in one neck; so that with one swift blow of the sword, I could decapitate them all.” Fantasies are often more fruitful than truths, and the Romans, it must be said, were never comfortable with Divine prerogatives. Most of all, they wanted to believe that their emperor was, like them, an “equal among equals.” Other emperors had encouraged this fantasy. So … at 37 years of age, I, Caligula the God, was murdered by officers of the Praetorian Guard, it has been said, for purely personal reasons. What a joke! Cassius Chaerea, joined by others, did the deed. Suetonius, who sometimes told the truth, claims Cassius had been stung by my caustic wit and nursed in his shrunken soul a suitable revenge. We had known each other since infancy. How ironic that it was my many attempts to put the two of us on the same footing – my joking – that finally did me in. In the service of his country, Chaerea had suffered an unfortunate wound in his genitallia. Whenever Chaerea was on duty, I gave out the watchwords “Priapus,” which means “erection,” or Venus,” Roman slang indicating a “eunuch.” Late in January, Chaerea requested the watchword of me, and I responded as usual. I had been addressing an acting troupe of young men. Enraged, Chaerea struck the first blow, and before my German guard could respond, the other conspirators quickly moved in and slew me. They carved me up good. Another conspirator, Cornelius Sabinus, murdered my wife and disposed of my infant daughter by smashing her skull against a wall. I had become emperor at thirty-seven, and was ghosted after nine short years. The good die young, don’t they?

It was revenge that killed the God, the pedestrian snit of a former school chum. Can you believe it? We Romans love our revenge more than life itself; a dish, it is said, better served cold. And it is this emotion, coiled in the heart like a serpent, that explains everything you need to know about the God Caligula, whose life went by contraries.

An Afterword by Chaerea

Don’t believe a word that bitch says. It’s true he lived his life by contraries – because he was perverse. He was always so, even as a young frightened boy. And it’s true that those in Rome who often claimed to be Republicans were no friends of the Republic; a Republic would have swept the whole lot of them into the dustbin. And that bit about revenge – too true. Of all of us, Caligula was the most artful in his vengeance. Vengeance is the justice of the powerless. But Caligula was not powerless, and his vengeance was not just. The very fact that it was not just was to him a spur and a permission. There was no bar he would not cross; his only friends were sycophants and actors. But what is an actor? A mask, an empty vessel, a significant gesture. How he acted! What a show he put on! Vengeance was his audience, Rome his theatre. Two things you must know about Caligua: First, that he was a sublime actor; second, that he told the truth, and told it in such a way that no one would believe him.

Stalin

Khrushchev, that clown, ruined everything. (He wiggles his little finger) With this little finger, I could have destroyed him … if I had not died. The tragedy of my life was that I died. Listen to him, this clown, bloviating to the 20th Party Congress in 1956 on the Personality Cult and its Consequences. (He reads from the speech): “We have to consider seriously and analyze correctly this matter in order that we may preclude any possibility of a repetition in any form whatever of what took place during the life of Stalin, ... who practiced brutal violence, not only toward everything which opposed him, but also toward that which seemed, to his capricious and despotic character, contrary to his concepts. Stalin acted not through persuasion, explanation and patient cooperation with people, but by imposing his concepts and demanding absolute submission to his opinion. Whoever opposed these concepts or tried to prove his [own] viewpoint and the correctness of his [own] position was doomed to removal from the leadership collective and to subsequent moral and physical annihilation." … Brutal violence, eh? The sniveling little turd. We used to make Nikita dance for us. I’d call him on the phone, usually late at night. Well you know, when you got a call from Stalin, you were instantly apprehensive. “What does the ogre want me for?” They knew that Stalin, the man of steel, rarely called to chit-chat. “Nikita, we need you here.” And so his roundness would scurry over. “Nikita, dance for us.” And then, after we had our fun with him, we’d all settle down to watch a gangster movie from Hollywood. Everyone would breathe a sign of relief; at least this night won’t end for me in the Lubyanka … Every great country should have a Hollywood and a Lubyanka. With a proper propaganda instrument and an effective rack, I could have ruled the world. But this Khrushchev: There was always something odd about him – his eyes; they were not stone dead. Behind them was a little shiver of joy. Even when he danced, in his humiliation, his eyes danced too. Now, Lavrentiya Beriya had the eyes of a dead fish. He was a competent administrator too, a flawed revolutionary. The true revolutionary, the indispensable foot soldier -- not the always disposable theoretician – is like one of those Russian boxes within boxes; you open one that reveals another inside, and yet another inside that – mystery within mystery. It is proper for the Father of his people to present a mysterious face to his children. No man willingly becomes the servant of the thing he knows, because as soon as you know something, you attain mastery over it. Mystery – capriciousness, some people called it – and terror, always terror, were my true ministers of state. The people, busy about their lives, will always be easy to control; I never once worried about them. But these viperous theoreticians represented a danger to me and to the Soviet State. I dealt with them … capriciously. Trotsky, that blockhead, I dispatched by sending an assassin to Mexico, where he was hiding out, awaiting an opportunity. Trotsky went there to escape this (He wiggles his little finger), but our assassin found him and parted his hair with an ice axe. Tito, on the other hand, survived the assassins we sent to Yugoslavia. None of them were successful. One day I received a note from Tito. Comrade Stalin, it said, if you send one more assassin here, I will send to Moscow one man with one pistol and one bullet – and he will not fail. Who needed that? A most unaccommodating man was Tito. We tossed him out of the Cominform. But after I died, he snuck in through a back window, with Khrushchev’s blessing. Trotsky’s assassin was convicted of murder and sentenced to prison in Mexico for 20 years; then, in 1953, ten years after the assassination, his true identity was discovered. His NKVD connections had remained hidden until after the fall of the Soviet Union. Can you imagine? Now, that assassin was a formidable revolutionary: Tell him to go and he goes; tell him to come and he comes … Ah, it was wonderful to be alive before the walls came crashing down – at least for me. We hid everything in broad daylight; no one noticed. We knew how to shut up and, more importantly, how to shut others up – even Westerners not entirely committed to the Soviet vision. If you want to know how it is possible to tuck under a rug a few million corpses without anyone noticing the lump, ask Khrushchev, my man in Ukraine during the famine and subsequent purges that followed in the 30’s and 40’s. Of course, I have no right to cry “hypocrite” in connection with all this. But it would be criminal of me not to mention that Khrushchev, who denounced me for brutal crimes committed against certain anti-soviet elements, was my primary instrument of destruction in Ukraine. And what an efficient turd he was! How proficiently he set about the business of destroying his own back yard! Khrushchev’s parents, you know, were agricultural peasants in Ukraine. He was never able entirely to kick the clogs of dirt from his shoes. He was barely literate until he reached manhood, though few regarded him as stupid. No man who crawls over so many corpses to become Premier of the Soviet Union may be called stupid. Let’s see: I have a list here of Krushchev’s casualties in Ukraine. (Reading from a report) “Human deaths, 4,800,000; livestock dead, 5,300,000 horses, 8,600,000 cattle, 7,000,000 swine …” – not a bad job. Pity the swine did not include Krushchev. That is what it took in the golden years of the Soviet Union to subdue nations clinging by their bloody fingertip to outmoded forms; for there was no question that the future was our. All this earned me the title: “Stalin, Breaker of Nations.” Krushchev was more modestly known as “The Butcher of Ukraine.” We waded through oceans of blood together, Krushchev and I – Beriya too. In the end, I also became a victim. Me, can you believe it? Krushchev and Beriya had learned their lessons well. They got me with rat poison; poetic justice, some said. And then Krushchev got Beriya. More poetic justice. The Soviet Union stumbled forward under Krushchev’s stewardship; he was followed by others, each softer and more merciful than his predecessor, and finally it ended in that swamp of sympathy -- Michael Gorbachov… Terror, terror and fear were the cross joists of our structure. Remove them and the whole edifice was bound to collapse. Before me there were other Russians who inspired fear; believe me, Ivan the Terrible was no slouch in this regard. But none used terror so efficiently. During the famine in Ukraine, there was an Englishman in Moscow who I thought understood me. “Watch Stalin,” he said to the West, “he’ll yoke the peasants to the plows” -- to accomplish my Five Year Plan. And later, visiting his friends in the United States, some of whom were queasy about the number of corpses upon which the Five Year Plan was built, he’d say, “Well, you can’t make omelets without breaking eggs.” I liked that. But the Plan was a convenient mask. So long as Stalin was pulling Russia into the 20th century by its long beard, the West seemed to understand well enough. And then there was the depression, which helped to draw people’s attention away from the work of revolution. Really -- we got away with murder. Apologists popped out of the Western woodwork; one could see that enlightened opinion was with us. We hid everything in plain sight; no one saw. People see what they want to see. In the West, they saw Stalin fighting Hitler, and forgot all about the pact we had formed with the Fuehrer, which was easily repudiated. Over here of course, the people saw what we wanted them to see. Forbidden sights led straight to the Lubyanka. Terror focuses the mind wonderfully. The curtain was rung in by the denunciations of the terrorists. It became possible to think, to breathe. Finis! … What a run though: An Empire of lies and terror such as the world has not seen since Cassius Chaerea murdered Caligula.

An Afterword by Gareth Jones

We were a small knot of journalists living, thinking and writing together in Moscow in the early 1930’s. Some – Malcom Muggeridge, for instance – came from the socialist camp. Muggeridge’s wife was related to the Webbs, Sidney and Beatrice, English Fabians, like George Bernard Shaw, who later on would play a walk on role in the Terror Famine. The event that parted us was the 1932-33 famine itself, not the first time that food had been used as a weapon of war by the soviets… To bring Ukraine within the soviet orbit, Stalin knew he would have to destroy all resistance. First he and his agents decapitated Ukraine: He murdered all the intellectuals – teachers, scientists, politicians, the clergy, anyone attached to the nation through their remembered affections. The peasantry was a hard nut to crack. From Roman times until the Terror Famine, Ukraine was known as “the bread basket of Europe.” Under cover of modernization, Stalin’s Five Year Plan, private farms were displaced by collectives. When the peasants proved intractable, Stalin destroyed them by creating and sustaining a famine. Communist cadres went into the villages and collected all the seed grain for the next year; they even destroyed the ovens used by the peasants to make bread. Famine stretched its boney hand over Ukraine. Whole villages died out; the trees were stripped bare by starving peasants who boiled leaves for nourishment. Rotting corpses of people and farm animals made the air unbreathable. That is what was covered from the rest of the world by the mask of Stalin’s Five Year Plan – murder on a mass scale. I saw what lay behind the mask when I defied the censors in Moscow, boarded a train and went into the countryside; so did Muggeridge. And we saw the sickening sight, Stalin’s hand lying over Ukraine, reduced to swollen belies and silent screams. We got the story out, Muggeridge in diplomatic pouches. Much good it did… We tried to say the truth, but it was smothered with lies, manufactured most effectively by Walter Duranty, the chief correspondent in Russia for the New York Times. Other journalists called him “The Great Durranty.” Muggeridge called him the worst pathological liar he had ever met in all his years in journalism. Duranty knew about the famine but suppressed news of it in his dispatches to the Times. Privately, he guessed that as many as six million people died between 1932-32; publicly, he joked that “you couldn’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.” For his reportage on Stalin’s Five Year Plan, Durranty was awarded a Pulitzer Prize. It was a prize earned at a great price. Stalin himself finally was murdered by two of his henchmen, Beryia and Krushchev. Funny, Beryia kicked the corpse and swore at it. But when it twitched, probably the result of involuntary movement, the marrow of his bones ran cold, and he ran off. That, at least is what Krushchev said. As for myself, I went to China following Moscow, and here I was murdered by communist bandits. Such were the times we lived in – bloody Times. I received no Pulitzer Prize.

c2006 Don Pesci

Comments